October 21, 2009

Autumn clouds and floods

More writeups of the Cloud Intelligence symposium at Ars Electronica, with videos and presentations. David Sasaki has a writeup of the symposium.

More writeups of the Cloud Intelligence symposium at Ars Electronica, with videos and presentations. David Sasaki has a writeup of the symposium.

My presentation on cloud superintelligence can be seen here.

Looking back at this event and the Singularity Summit, I have become more and more convinced that we need to examine the alternative to I. J. Good's concept of "intelligence explosion" in the form of an "intelligence flood". As he wrote:

"Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind."

Now consider a collective intelligence - a large bunch of humans connected using suitable software and social networks. I think it is true that such a collective intelligence clearly is ultraintelligent in most respects. It might not be much better than its smartest members at inventing quantum gravity, but it is able to manage enormous projects and handle distributed knowledge far beyond human capacity. If it can be expanded without losing capability, then we have a form of intelligence explosion. This is what drives the radical growth in Robin Hanson's upload economy model, as well as his AI growth paper - not supreme intelligence, just a lot more of it. The real issues here is 1) how hard it is to expand a collective intelligence without losing capability, 2) what domains are easy or hard for collective intelligences and 3) whether expanding collective intelligences is in the easy or hard category. I would guess it is easy, but I am not 100% sure.

October 16, 2009

Following the tweets

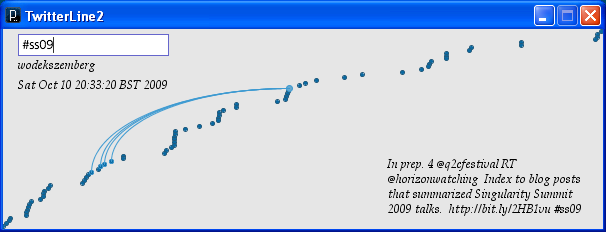

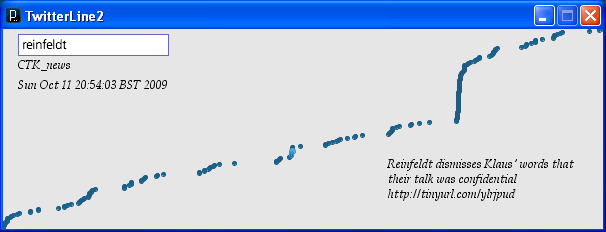

Here is a little Processing application I have put together to visualize Twitter activity. You enter a search term in the box and it shows you tweets that match. As you mouse over the tweets you can see their originator, time and content as well as possible links to previous tweets based on text overlap. .Zip download for Windows, Mac and Linux (just select the right subdirectory and uncompress; I have so far just tested it for Windows)

Time posted is horizontal, while the order of the tweets is vertical. A steady stream of tweets will be a diagonal line, while bursts will produce more vertical slopes and pauses horizontal slope. For example, in the image below there was a television debate between Fredrik Reinfeldt (the Swedish prime minister) and Mona Sahlin (the opposition leader), producing a burst of twittering on the right side.

If you press '+' (while the focus is in the window but not in the text field) the app will try downloading more pages from Twitter, while '-' reduces the number. '*' and '/' increases and decreases the sensitivity to text overlap.

The reason it is an application and not an applet is that this way I do not have to self-sign the .jar file (applets are not normally allowed to connect to outside servers like twitter, and getting around this would take more of my limited time). The program uses the Interfascia and Twitter4J libraries.

Serious reading

Greg Egan comments on a review hatchet job, pointing out something relevant and interesting:

Greg Egan comments on a review hatchet job, pointing out something relevant and interesting:

This leaves me wondering if they've really never encountered a book before that benefits from being read with a pad of paper and a pen beside it, or whether they're just so hung up on the idea that only non-fiction should be accompanied by note-taking and diagram-scribbling that it never even occurred to them to do this. I realise that some people do much of their reading with one hand on a strap in a crowded bus or train carriage, but books simply don't come with a guarantee that they can be properly enjoyed under such conditions.

In fact, many aficionados of "real" literature claim the true pleasure lies in discovering the hidden structures under the surface. So why are not more people taking notes when reading fiction? Greg Egan may be unique in that you would actually benefit from solving equations in parallel with reading, but I would expect many novels would benefit from readers extending their effective working memory. After all, who knows where Captain Yakovlev will turn up later and what he will symbolize?

[ Personally I found Incandescence a mildly interesting read, but it did not grab me. While I agree with Egan that mathematics and the natural sciences are intrinsically interesting and that telling the story of how science develops can be riveting, I don't think I am that much of an orbit guy. Geodesics are much more fun when you bundle them. Give me a novel about neuroscience, causality or topology any day.

...Actually, there is one story about orbits that is truly gripping: Arthur C. Clarke's "Maelstrom II". And it is completely Newtonian! Coming to think of it, Poe's original story was a somewhat dramatized depiction of experimental hydrodynamics. ]

October 15, 2009

A taxonomy of philosophy

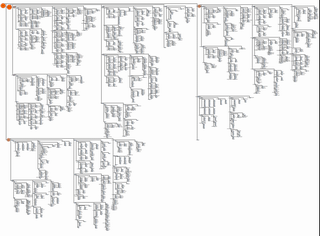

David Chalmers and David Bourget have developed a taxonomy of philosophy for use in the PhilPapers project. I couldn't resist plotting them, either as a bubbly tree or as a more compact tree (pdfs).

David Chalmers and David Bourget have developed a taxonomy of philosophy for use in the PhilPapers project. I couldn't resist plotting them, either as a bubbly tree or as a more compact tree (pdfs).

It is fun to see just how much is under the heading "philosophy" - especially since I suspect there is plenty left out in this hierarchy. Many branches go fairly deep within other fields.

Quantum suicide is painless (but unlikely)

Practical Ethics: If God hates the Higgs boson, we can build paradise on Earth - just a little note that if the retrocausation anti-Higgs theory of why the LHC have had trouble is right, we can use it for global quantum suicide paradise engineering. But my previous calculation suggests that it is many mishaps too early to break out the champagne.

Practical Ethics: If God hates the Higgs boson, we can build paradise on Earth - just a little note that if the retrocausation anti-Higgs theory of why the LHC have had trouble is right, we can use it for global quantum suicide paradise engineering. But my previous calculation suggests that it is many mishaps too early to break out the champagne.

October 14, 2009

Old errors

Thermodynamic Cost of Reversible Computing is making the rounds on Slashdot.

Thermodynamic Cost of Reversible Computing is making the rounds on Slashdot.

What the paper shows is basically that reversible computation with errors has to dissipate energy. Even an amateur like me had noted back in 99 that error correction requires paying kTln(2) J per fixed bit. When doing reversible computation the corrections will occur during the computation and hence induce a certain average cost per computation. The temperature here is not necessarily physical temperature but the "noise temperature" defined based on the entropy production.

For a qubit being flipped about they derive an lower bound on energy cost to be hR2ε/2 Watts where R is the rate of computations and ε the error probability per computation. In general, the dissipation grows with the square of the computation rate.

So if I have energy E and want to make the most calculations, I should slow down indefinitely. This is of course why I can never meet a deadline. However, eventually I will reach the dissipation limit I considered in the 99 paper of random bit flips - storing information for a long time costs too. So the optimal rate if I have plenty of time is going to be the rate where I produce equal amounts of heat from processing and from maintaining my stored bits. On the other hand, if I have a time limit T in addition, then I should use up all the energy by time T, and hence have a computation rate of sqrt(E/hT).

October 11, 2009

How to survive among unfriendly superintelligences

A mouse has set up operations in our kitchen. The humans in the house (all with the best academic qualifications - we have three professors) are trying to catch it. So far, the mouse is winning.

A mouse has set up operations in our kitchen. The humans in the house (all with the best academic qualifications - we have three professors) are trying to catch it. So far, the mouse is winning.

It is an interesting example of how a "lesser" being can prevail against beings far smarter than itself. The value of our time is so great that few of us are spending enough time trying to solve the problem well - the mouse represents a minor annoyance that we intellectually regard as a potentially serious problem but in practice have a hard time focusing on. Hence stupidities like giving it easily accessible non-trapped food.

I think we can learn from the mouse (and guerilla groups throughout history) that 1) if you can use the local geography to hide from easy attack, 2) make sure the enemy never have enough motivation to attack you using effective means (such as poison) you can likely survive among unfriendly super-minds. The only problem is that estimating the parameters of factor 2 will be very uncertain: the mouse is likely unaware that any sign of breeding or overt uncleanliness will move the conflict to defcon 1. A human versus a super-AI will have to guess what human activities actually interfere with the AI-activities and avoid them (as well as figure out what constitutes an easy attack). Not the safest of situations.

I would of course solve the problem by introducing a cat, but my fellow superintelligences are less in favour. Meanwhile the mouse is happily eyeing my muesli.

Epilogue, November 7 2009: Today the story ended. Tragically, while changing rubbish bags I accidentally crushed the little thing. So I defeated the mouse - not by design or cleverness, just strength and carelessness. So when dealing with unfriendly superintelligences, remember that just because you are under their motivational radar doesn't mean you are safe from their actions. But they might discuss you and your demise in media you cannot even conceive of, in order to learn lessons that are even stranger.

October 10, 2009

Bad science and policy

Practical Ethics: Protecting our borders with snake oil - the recent Human Provenance pilot project debacle, where the UK Border Agency looked into using DNA data to determine the "true" nationality (as if genetics and ethnicity encoded national status), demonstrates that governments are very eager to buy scientific snake oil. Or more properly, want to adopt technologies that are *really* not ready for prime time. It is one thing to develop a new technology as needed, another thing entirely to try to apply something that has not yet proven itself.

Practical Ethics: Protecting our borders with snake oil - the recent Human Provenance pilot project debacle, where the UK Border Agency looked into using DNA data to determine the "true" nationality (as if genetics and ethnicity encoded national status), demonstrates that governments are very eager to buy scientific snake oil. Or more properly, want to adopt technologies that are *really* not ready for prime time. It is one thing to develop a new technology as needed, another thing entirely to try to apply something that has not yet proven itself.

I just fear that the public and policy-makers are less interested in getting real results and more in getting impressive actions done. How to get everyone to desire evidence based policy? It will cost resources, yet the savings will often be less clear.

October 08, 2009

A singular event

Just back from the Singularity Summit and subsequent workshop. I am glad to say it exceeded my expectations - the conference had a intensity and concentration of interesting people I have rarely seen in a general conference.

Just back from the Singularity Summit and subsequent workshop. I am glad to say it exceeded my expectations - the conference had a intensity and concentration of interesting people I have rarely seen in a general conference.

I of course talked about whole brain emulation, sketching out my usual arguments for how complex the undertaking is. Randall Koene presented more on the case for why we should go for it, and in an earlier meeting Kenneth Hayworth and Todd Huffman told us about some of the simply amazing progress on the scanning side. Ed Boyden described the amazing progress of optically controlled neurons. I can hardly wait to see what happens when this is combined with some of the scanning techniques. Stuart Hameroff of course thought we needed microtubuli quantum processing; I had the fortune to participate in a lunch discussion with him and Max Tegmark on this. I think Stuart's model suffers from the problem that it seems to just explain global gamma synchrony; the quantum part doesn't seem to do any heavy lifting. Overall, among the local neuroscientists there were some discussion about how many people in the singularity community make rather bold claims about neuroscience that are not well supported; even emulation enthusiasts like me get worried when the auditory system just gets reduced to a signal processing pipeline.

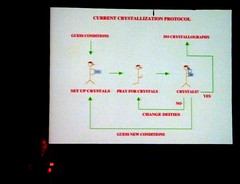

Michael Nielsen gave a very clear talk about quantum computing and later a truly stimulating talk on collaborative science. Ned Seeman described how to use DNA self assembly to make custom crystals. William Dickens discussed the Flynn effect and what caveats it raises about our concepts of intelligence and enhancement. I missed Bela Nagy's talk, but he is a nice guy and he has set up a very useful performance curve database.

Michael Nielsen gave a very clear talk about quantum computing and later a truly stimulating talk on collaborative science. Ned Seeman described how to use DNA self assembly to make custom crystals. William Dickens discussed the Flynn effect and what caveats it raises about our concepts of intelligence and enhancement. I missed Bela Nagy's talk, but he is a nice guy and he has set up a very useful performance curve database.

David Chalmers gave a talk about the intelligence explosion, dissecting the problem with philosophical rigour. In general, the singularity can mean several different things, but it is the "intelligence explosion" concept of I.J. Good (more intelligent beings recursively improving themselves or the next generation, leading to a runaway growth of capability) that is the most interesting and mysterious component. Not that general economic and technological growth, accelerating growth, predictability horizons and the large-scale structure of human development are well understood either. But the intelligence explosion actually looks like it could be studied with some rigour.

Several of the AGI people were from the formalistic school of AI, proving strict theorems on what can and cannot be done but not always coming up with implementations of their AI. Marcus Hutter spoke about the foundations of intelligent agents, including (somewhat jokingly) whether they would exhibit self-preservation. Jürgen Schmidhuber gave a fun talk about how compression could be seen as underlying most cognition. It also included a hilarious "demonstration" that the singularity would occur in the late 1500s. In addition, I bought Shane Legg's book Machine Super Intelligence. I am very fond of this kind of work since it actually tells us something about the abilities of superintelligences. I hope this approach might eventually tell us something about the complexity of the intelligence explosion.

Stephen Wolfram and Gregory Benford talked about the singularity and especially about what can be "mined" from the realm of simple computational structures ("some of these universes are complete losers"). During dinner this evolved into an interesting discussion with Robin Hanson about whether we should expect future civilizations to look just like rocks (computronium), especially since the principle of computational equivalence seems to suggest than there might not be any fundamental difference between normal rocks and posthuman rocks. There is also the issue of whether we will become very rich (Wolfram's position) or relatively poor posthumans (Robin's position); this depends on the level of possible coordination.

Stephen Wolfram and Gregory Benford talked about the singularity and especially about what can be "mined" from the realm of simple computational structures ("some of these universes are complete losers"). During dinner this evolved into an interesting discussion with Robin Hanson about whether we should expect future civilizations to look just like rocks (computronium), especially since the principle of computational equivalence seems to suggest than there might not be any fundamental difference between normal rocks and posthuman rocks. There is also the issue of whether we will become very rich (Wolfram's position) or relatively poor posthumans (Robin's position); this depends on the level of possible coordination.

In his talk Robin brought up the question of who the singularity experts were. He noted that technologists might not be the only one (or even the best ones) to say things in the field: the social sciences have a lot of things to contribute too. After all, they are the ones that actually study what systems of complex intelligent agents do. More generally one can wonder why we should trust anybody in the "singularity field": there are strong incentives for making great claims that are not easily testable, giving the predictor prestige and money but not advancing knowledge. Clearly some arguments and analysis does make sense, but the "expert" may not contribute much extra value in virtue of being an expert. As a fan of J. Scott Armstrong's "grumpy old man" school of future studies I think the correctness of predictions have very rapidly decreasing margin, and hence we should either look at smarter ways of aggregating cheap experts, aggregating multi-discipline insights or make use with heuristics based on solid evidence or the above clear arguments.

Gregory Benford described the further work derived from Michael Rose's fruit flies, aiming at a small molecule life extension drug. Aubrey contrasted the "Methuselarity" with the singularity - cumulative anti-ageing breakthroughs seem able to produce a lifespan singularity if they are fast enough.

Gregory Benford described the further work derived from Michael Rose's fruit flies, aiming at a small molecule life extension drug. Aubrey contrasted the "Methuselarity" with the singularity - cumulative anti-ageing breakthroughs seem able to produce a lifespan singularity if they are fast enough.

Peter Thiel worried that we might not get to the singularity fast enough. Lots of great soundbites, and several interesting observations. Overall, he argues that tech is not advancing fast enough and that many worrying trends may outrun our technology. He suggested that when developed nations get stressed they do not turn communist, but may go fascist - which given modern technology is even more worrying. "I would be more optimistic if more people were worried". So in order to avoid bad crashes we need to find ways of accelerate innovation and the rewards of innovation: too many tech companies act more like technology banks than innovators, profiting from past inventions but now holding on to business models that should become obsolete. At the same time the economy is implicitly making a bet on the singularity happening. I wonder whether this should be regarded as the bubble-to-end-all-bubbles, or a case of a prediction market?

Brad Templeton did a great talk on robotic cars. The ethical and practical case for automating cars is growing, and sooner or later we are going to see a transition. The question is of course whether the right industry gets it. Maybe we are going to see an iTunes upset again, where the car industry gets eaten by the automation industry?

Anna Salamon gave a nice inspirational talk about how to do back-of-the-envelope calculations about what is important. She in particular made the point that a lot of our thinking is just acting out roles ("As a libertarian I think...") rather than actual thinking, and trying out rough estimates may help us break free into less biased modes. Just the kind of applied rationality I like. In regards to the singularity it of course produces very significant numbers. It is a bit like Peter Singer's concerns, and might of course lead to the same counter-argument: if the numbers say I should devote a *lot* of time, effort and brainpower to singularitian issues, isn't that asking too much? But just as the correct ethic might actually turn out to be very heavy, it is not inconceivable that there are issues we really ought to spend enormous effort on - even if we do not do it right now.

Anna Salamon gave a nice inspirational talk about how to do back-of-the-envelope calculations about what is important. She in particular made the point that a lot of our thinking is just acting out roles ("As a libertarian I think...") rather than actual thinking, and trying out rough estimates may help us break free into less biased modes. Just the kind of applied rationality I like. In regards to the singularity it of course produces very significant numbers. It is a bit like Peter Singer's concerns, and might of course lead to the same counter-argument: if the numbers say I should devote a *lot* of time, effort and brainpower to singularitian issues, isn't that asking too much? But just as the correct ethic might actually turn out to be very heavy, it is not inconceivable that there are issues we really ought to spend enormous effort on - even if we do not do it right now.

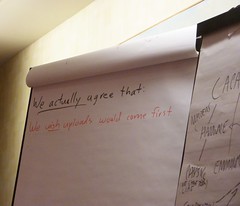

During the workshop afterwards we discussed a wide range of topics. Some of the major issues were: what are the limiting factors of intelligence explosions? What are the factual grounds for disagreeing about whether the singularity may be local (self-improving AI program in a cellar) or global (self-improving global economy)? Will uploads or AGI come first? Can we do anything to influence this?

During the workshop afterwards we discussed a wide range of topics. Some of the major issues were: what are the limiting factors of intelligence explosions? What are the factual grounds for disagreeing about whether the singularity may be local (self-improving AI program in a cellar) or global (self-improving global economy)? Will uploads or AGI come first? Can we do anything to influence this?

One surprising discovery was that we largely agreed that a singularity due to emulated people (as in Robin's economic scenarios) has a better chance given current knowledge than AGI of being human-friendly. After all, it is based on emulated humans and is likely to be a broad institutional and economic transition. So until we think we have a perfect friendliness theory we should support WBE - because we could not reach any useful consensus on whether AGI or WBE would come first. WBE has a somewhat measurable timescale, while AGI might crop up at any time. There are feedbacks between them, making it likely that if both happens it will be closely together, but no drivers seem to be strong enough to really push one further into the future. This means that we ought to push for WBE, but work hard on friendly AGI just in case. There were some discussions about whether supplying AI researchers with heroin and philosophers to discuss with would reduce risks.

All in all, some very simulating open-ended discussions at the workshop with relatively few firm conclusions. Hopefully they will appear in the papers and essays the participants will no doubt write to promote their thinking. I certainly know I have to co-author a few with some of my fellow participants.