September 30, 2008

More Fish Oil!

Practical Ethics: The price of ignorance: the Durham study and research ethics - I have blogged about the study before, but the latest revelations cry out for more blogging. I really hope this whole affair ends up in the textbooks as a clear example of how to not do science.

September 27, 2008

The Red Flux: Does the Swedish Social Democrat Youth Association Promote Bioterrorism?

A few weeks ago a shigella outbreak occurred at the Swedish Business Association, making about 140 people sick. Recently some leftist group apparently claimed responsibility on a web page, making the security police investigate. The mortality of shigellosis in developed countries is ~1%, so statistically there could have been about 1.4 fatalities in the outbreak. Now the social democratic youth organization (SSU) promises a bouquet of roses to whoever caused the outbreak. Emma Lindqvist, chairwoman of SSU Stockholm says: "We are of course not condoning methods like this, capitalism is to be abolished without biological warfare. But sick practical jokes like this should be promoted with a bit of flowers."

A few weeks ago a shigella outbreak occurred at the Swedish Business Association, making about 140 people sick. Recently some leftist group apparently claimed responsibility on a web page, making the security police investigate. The mortality of shigellosis in developed countries is ~1%, so statistically there could have been about 1.4 fatalities in the outbreak. Now the social democratic youth organization (SSU) promises a bouquet of roses to whoever caused the outbreak. Emma Lindqvist, chairwoman of SSU Stockholm says: "We are of course not condoning methods like this, capitalism is to be abolished without biological warfare. But sick practical jokes like this should be promoted with a bit of flowers."

The UN defines terrorism as "Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes..." and more academically as "Terrorism is an anxiety-inspiring method of repeated violent action, employed by (semi-) clandestine individual, group or state actors, for idiosyncratic, criminal or political reasons, whereby - in contrast to assassination - the direct targets of violence are not the main targets. The immediate human victims of violence are generally chosen randomly (targets of opportunity) or selectively (representative or symbolic targets) from a target population, and serve as message generators."

By these definitions, if the shigellosis outbreak was deliberate, it seems to have been terrorism. Maybe if the goal was just a direct attack against the Swedish Business Association it would have been a lesser crime. The UN resolution continues "...are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or other nature that may be invoked to justify them" - something that most people would agree with. But apparently SSU Stockholm finds bioterrorism at least a sick practical joke worthy of symbolic rewards.

Given the rapid growth of bioterrorism risks we are soon likely to rue a few other "practical jokes".

September 26, 2008

Petrov Day

Eliezer reminds us that today is Petrov Day. That is, on this day in 1983 Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov prevented a pre-emptive nuclear strike against the US.

During our workshop on existential risks this summer we discussed Petrov and other heroes of Armageddon-averting. The most annoying thing was that despite having a room crammed with experts on this kind of thing, we did not even know the names of some of Petrov's peers. I think one of the simplest, and most constructive ideas that came up during the meeting would be to try to set up a serious prize for averting an imminent threat to human survival, and use it to make everybody aware that real heroes walk the earth. Even if their heroism consists of not having done something.

September 22, 2008

Bayes, Moravec and the LHC: Quantum Suicide, Subjective Probability and Conspiracies

The recent transformer trouble at the LHC has got many commenters to remember the somewhat playful scenario in Hans Moravec's Mind Children (1988): a new accelerator is about to be tested when it suffers a fault (a capacitor blows, say). After fixing it, another fault (a power outage) stops the testing. Then a third fault, completely independent of the others. Every time it is about to turn on something happens that prevents it from being used. Eventually some scientists realize that sufficiently high energy collisions would produce a vacuum collapse, destroying the universe. Hence the only observable outcome of the experiment occurs when the accelerator fails, all other branches in the many-worlds universe are now empty. (This then leads up to a fun discussion on quantum suicide computation)

The recent transformer trouble at the LHC has got many commenters to remember the somewhat playful scenario in Hans Moravec's Mind Children (1988): a new accelerator is about to be tested when it suffers a fault (a capacitor blows, say). After fixing it, another fault (a power outage) stops the testing. Then a third fault, completely independent of the others. Every time it is about to turn on something happens that prevents it from being used. Eventually some scientists realize that sufficiently high energy collisions would produce a vacuum collapse, destroying the universe. Hence the only observable outcome of the experiment occurs when the accelerator fails, all other branches in the many-worlds universe are now empty. (This then leads up to a fun discussion on quantum suicide computation)

As Eliezer and other bright people realize, one transformer breaking before even the main experiments is not much evidence. But how much evidence (in the form of accidents stopping big accelerators) would it take to buy the anthropic explanation above?

Here is a quick Bayesian argument: Let D be that the accelerator is dangerous, N be that N accidents have happened so far.

P(D|N) = P(N|D)P(D)/P(N) =P(N|D)P(D)/ [P(N|D)P(D) + P(N|-D)P(-D) ]

Since P(N|D)=1 by assumption we get

P(D|N)=P(D)/ [P(D) + P(N|-D)(1-P(D)) ]

Let X=P(D) be our prior probability that high energy physics is risky in this way, and Y=P(1|-D) be the probability that one accident happen in the non-dangerous case. We also assume the accidents are uncorrelated, so P(N|-D)=Y^N. Then we get

P(D|N)=X/ [X + (1-X) Y^N ]

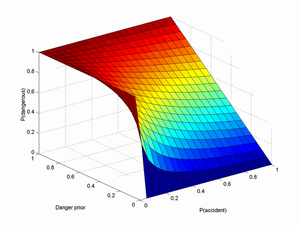

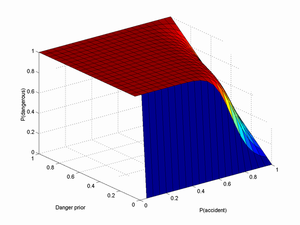

Below is a plot for N=1 and another one for N=10:

I think Y can safely be assumed to be pretty big, perhaps ~1/2 or even more. X depends on your general faith in past theoretical papers showing the safety of accelerators. In particular, I think Hut, P. and M. J. Rees (1983). "How Stable Is Our Vacuum." Nature 302(5908): 508-509 makes a very solid argument against vacuum decay (especially when combined with Tegmark, M. and N. Bostrom (2005). "Is a doomsday catastrophe likely?" Nature 438(7069): 754-754), so X < 10-9.

Plugging in N=1,X=10-9 and Y=0.5 gives us P(D|N)=2*10-9. Wow! A doubling of the estimate, all because of a transformer. Claiming the closure of the SSC is another datapoint would bring up the chance to 4 chances in a billion.

In fact, I think this is a gross overestimate because the X above is the risk per year; we didn't even get one second of collisions. If the risk is actually on the order of one disaster per year, we should expect to run the accelerator for about half a year before something happens preventing the collision. If the risk is much higher, then we should expect an earlier shut-down. So given that we got one or two early shut-downs, we should (if we believe they were due to branch-pruning) think the risk is much higher, say about 31 million times higher (number of seconds in a year) or more. But if we were to live in such a dangerous universe where every TeV interaction had a decent chance of destroying its future lightcone, then the Tegmark and Bostrom argument suggests that we are in a really unusual position. So getting a consistent and likely situation is hard if you think disaster is likely.

So, how many accidents would be needed to make me think there was something to the disaster possibility? Using the above estimates, I find P(D|20)=0.001 and and P(D|30)=0.52. So if about 30 uncorrelated, random major events in turn prevent starting the LHC, I would have cause to start thinking there was something to the risk.

However, the likelihood of some prankster or anti-LHC conspiracy trying to trip me or the LHC people up seems to be larger than one chance in a billion per year. This would add an extra term to the equation, giving us P(D|N)=X/ [X + (1-X) (Y^N + Z) ] where Z is the probability of foul play. Adding just one chance in a billion reduces the P(D|30) estimate to 0.34, which is still pretty big. If it is one chance in 100 million it becomes 0.08, and one chance in 10 million gives 0.01. However, I think the chance for the existence of a conspiracy able to successfully cause 30 LHC shutdowns in a row (without anybody finding any evidence) is hardly on the order of one in 10 million.

In the unlikely case we actually get a high P(D) estimate, it might seem we have got a way of doing quantum suicide computing (connect it to a computer trying random solutions, destroy the universe if the wrong one is found, reap benefits in all remaining universes) or even terrorism prevention (automatically destroy all universes where terrorist attacks occur, to the surviving observers it will look like terrorism magically has ceased). Unfortunately Y is likely pretty big. We should hence expect to see a lot of universes where the LHC simply fails because of the usual engineering problems, and leaves us with the wrong solution or the aftermath of terrorism. Quantum suicide computing/omnipotence requires absurdly reliable equipment.

September 18, 2008

Designing Childhood's End

BTW, Dresden Codak's "Hob" is now concluded. If I ever get to run a singularity I will ask Aaron Diaz to design it.

BTW, Dresden Codak's "Hob" is now concluded. If I ever get to run a singularity I will ask Aaron Diaz to design it.

I'm increasingly convinced that design, in its broadest sense, is going to be crucial for the advanced technologies in the future. What is under the hood seldom matters as much for the eventual impact as how you can use it, regardless of whether it is cars, computers or nanomachines. Which means that we may need to be as careful in designing as we want to be about core abilities. Design is also closely related to legislation - certain design choices make some activities easy or hard to do regardless of whether they are "allowed", and also make different kinds of rules enforceable. Classic examples are of course the Internet and email. And as Peter S. Jenkins points out, a combination of design choices and early case law can set the legal principles underlying a whole technology.

The problem is that "get it right first" seldom works. Most complex or general-purpose technologies get developed by multiple interests and with their consequences extremely hard to predict. In fact, most likely all nontrival consequences are in general impossible to predict even in principle. We can make statements like "any heat engine doing needs a temperature difference to do work" even about unknown future super-steam engines, but even discovering this basic constraint required the development of thermodynamics as a consequence of developing the steam engines. I hence make the conjecture that the extent we can predict and constrain the use of future technologies is proportional to the amount of the technology we already have experience with.

That is why saying anything useful about self-improving AI is so hard today: we don't have any examples at all. We can say a few things about self-replicating machines, because we have a few examples, and this leads to things like the efficient replicator conjecture or the estimated M1/4 replication time scaling. We can say a lot more about future computers, but again many of the rules we have learned (like network externalities) do not constrain things much: we can just deduce that networks will be enormously more powerful than individual units, but this is not enough to tell us anything about what they will be used for. It however tells us that if we want to keep some activity less powerful, we need to limit its networking abilities - even limited knowledge can be somewhat useful.

So if we get a singularity, I think we can predict from experience, that we will make irreversible mistakes. If it is not the Friendly AI that acts up it will be the social use of nanotechnology or the emergent hyper-economy (and that leaves out the risk of something completely unexpected). I'm fairly confident that my conjecture is true for any level of intelligence (due to complexity constraints) so the superintelligences are going to mess things up in very smart ways too. So we better learn how to design systems and especially systems of systems that it is not the whole world if they fail or turn out to be suboptimal.

Childhood's end is to realize that choices matter and that you will be held responsible - but you don't know what to do. And there is nobody else you can ask.

So maybe in these last years of humanity's childhood we should focus on enjoying doing science to our cookies.

Synthetic ethics?

Eric Parens, Josephine Johnston and Jacob Moses ask in Nature Do We Need "Synthetic Bioethics"?

Their sensible conclusion is that inventing new sub-fields of (bio)ethics as soon as the scientists come up with a new concept might be good for job security but bad for ethics. After all, most of the questions dealt with are common to many areas and not just a particular one. Nanoethics and neuroethics should not come up with different answers just because of their names.

I had some similar sentiments a while ago about nanoethics and neuroethics. The best we can do is to use each field to focus on the questions that become really salient in the field.

Another dethronement of human uniqueness! (Yawn)

Probably something most dog owners know, but nice to see formally documented and tested: Dogs catch human yawns (Biology Letters 4:5 October 23, 2008, p446-448) It also contradicts earlier claims that yawn contagion is purely human or that it is just found among primates.

Probably something most dog owners know, but nice to see formally documented and tested: Dogs catch human yawns (Biology Letters 4:5 October 23, 2008, p446-448) It also contradicts earlier claims that yawn contagion is purely human or that it is just found among primates.

Some other interesting articles from the same journal:

Sea lice are good at escaping onto the predator when it eats their host

Immune response impairs learning in bumble-bees - there seems to be either competition for energy between the nervous system and the immune system, or some of the immune responses mess things up for the CNS.

The pattern of fossil feathers can likely be inferred - the dark in the fossils is apaprently remnants of melanosomes, showing where there were colour. It is hence possible to deduce feather patterns and possibly (using electron microscopy) even colouring.

The Robin Hood parasite - a plant parasite that has deleterious effects on the most fecund hosts and apparently beneficial effects on the least fecund hosts. The cause might be that the fecund host lines trade off their "immune system" for reproduction, or that the least fecund hosts overcompensate for the parasite damage.

More than 50% of old dinosaur species are actually invalid - but paleontology is getting better these days than the victorian bone-hunters. One should in any case not trust species lists too naively.

More than 50% of old dinosaur species are actually invalid - but paleontology is getting better these days than the victorian bone-hunters. One should in any case not trust species lists too naively.

Hierarchical social networks among mammals have the same scaling pattern - Each level of organisation is about 3 times as large as the previous, with the possible exception for orcas (where it is 3.8).

Female guppies select areas with higher predation risk to get away from sexual harassment - but on the other hand, females of swordtail fish prefer males with a particular spotted tail pattern that has a high risk of getting melanomas, hence keeping the otherwise detrimental gene in the population.

September 15, 2008

Cluedo in the brain

Practical Ethics: I suggest it was Professor Plum, in the library, with the arsenic: the unreliability of brain experience detection - I blog at Ethical Perspectives on the News about the recent conviction in Mumbai based on EEG evidence. Unsurprisingly I'm critical. This is one business where there are more companies than published papers.

Practical Ethics: I suggest it was Professor Plum, in the library, with the arsenic: the unreliability of brain experience detection - I blog at Ethical Perspectives on the News about the recent conviction in Mumbai based on EEG evidence. Unsurprisingly I'm critical. This is one business where there are more companies than published papers.

I'm pretty certain I could fool one of those detectors, especially if they actually do what they claim to do, detect memory retrieval. I would just retrieve memories linked to the neutral statements, and maybe mess up the non-neutral statements by considering their grammar. But given the biases this kind of setup invites, I think that in a real police investigation that would have much less effect than what the investigators would want as an outcome.

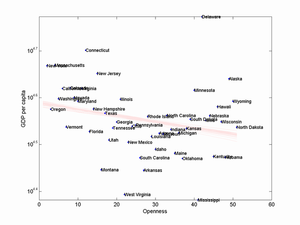

Openness is creative, but does it earn money?

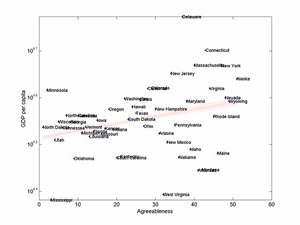

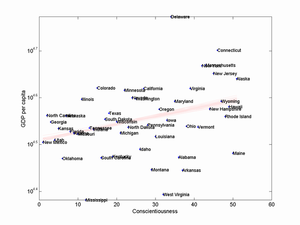

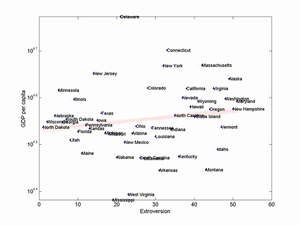

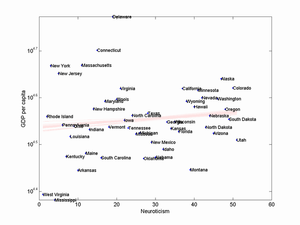

Gene Expression: New Yorkers do need to see their analysts points out an interesting paper: A Theory of the Emergence, Persistence, and Expression of Geographic Variation in Psychological Characteristics that tries to analyse why people differ psychologically in different parts of the US. For example, people might move to places where they fit in, or the environment may create certain personalities (and the environment may also be affected by personality as a feedback loop). Lots of fun stuff to play with.

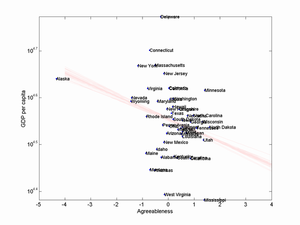

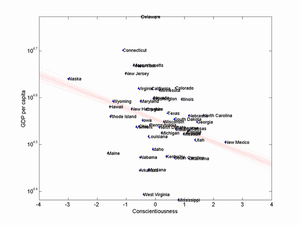

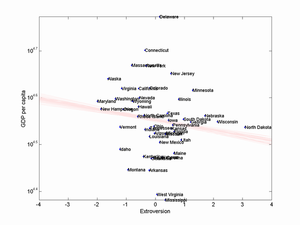

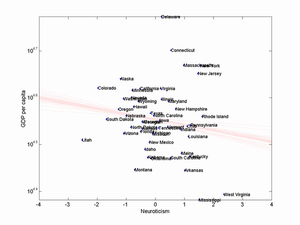

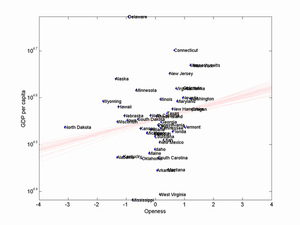

However, while the paper seemed to support Richard Florida's ideas about the bohemian advantage I wondered why they did not analyse the correlation with state GDP per capita. So I did a quick check myself.

I used log(GDP per capita) instead of raw GDP, since the multiplicative nature of GDP tends to skew things otherwise. I also left out Washington DC, since it is a clear outlier and tends to distort things.

Update: As noted by Nathaniel in the comments on Gene Expression I used state rank instead of z-scores, which more or less invalidates my original version (at the very least, the correlations change sign). Here is the new results with z-scores (old ones below the fold).

Correlation with log GDP: extroversion -0.15, agreeableness -0.32, conscientiousness -0.33, neuroticism -0.16 and openness 0.20.

I have plotted the different factors vs GDP below (click for a larger version), with a bundle of regression lines added (each corresponds to the data minus one state, thus showing a bit how stable the estimates are).

So the conclusion seems to be, yes, openness does improve GDP mildly. But agreeableness and conscientiousness are bad for it. Almost as strange.

Old, wrong results (do not use except as a warning to others!):

Extroversion correlated weakly positive (0.16), agreeableness moderately (0.31), conscientiousness moderately (0.34), neuroticism weakly (0.13) and openness negatively (-0.26). That seems odd.

I have plotted the different factors vs GDP below (click for a larger version), with a bundle of regression lines added (each corresponds to the data minus one state, thus showing a bit how stable the estimates are).

Maybe one reason for this result is that I'm not controlling for everything; in the paper they control for median income, percentage African Americans, residents with college degree and concentration in large cities. At least the first would wipe out the first-order effect. But it still seems somewhat odd that factors that correlate with patent production per capita seem anticorrelated with GDP.

On the other hand, maybe we should not be too surprised that average personality is not a strong predictor of GDP. It predicts various aspects of society, but it is these (together with other factors) that affect GDP. The factors themselves have no unitary influence. For example, high openness is probably good for creative work, but in the general population might promote credulity and criminality (0.42 correlation in the study, when controlling for demographic) that lower GDP.

September 13, 2008

The food tastes too good

Why are people getting obese? Could it be that they eat too much? Of course. And since it cannot be their fault it must be some food additive making them! Svenska Dagbladet runs a story Smakämne ökar risk att bli fet that claims the culprit is MSG, sodium glutamate.

Why are people getting obese? Could it be that they eat too much? Of course. And since it cannot be their fault it must be some food additive making them! Svenska Dagbladet runs a story Smakämne ökar risk att bli fet that claims the culprit is MSG, sodium glutamate.

The source is a study that examined Chinese villagers, comparing the users of MSG with the non-users. The users where heavier, and SvD claims that when controlling for caloric intake, MSG appears to produce obesity.

There are just a few major problems with this story. First, the article erroneously suggests that MSG is something "western", while it is actually quite the reverse. Much of the bad press of MSG is due to "Chinese restaurant syndrome", which has been attributed (with no demonstrated causal link) to MSG. In fact, of the villagers in the study 82.4% were adding MSG to their food.

(In this paper it is mentioned that 20% of test subjects react more weakly to the MSG taste than the rest; maybe this correlates with the ~80% use?)

Second, as junkfood science points out, the statistical method looks iffy. If there was a simple causal link the heavy users would be on average heavier than the nonusers (when controlling for food and exercise), but instead they found more obese people in the heavy user category than in the nonuser category (the averages did not differ much). Maybe some people are vulnerable to MSG, but there are strong confounders here. For example, heavier people tend to eat more, and would hence eat more MSG per day than small eaters.

Third, the news stories all love to depict MSG as something nasty and unnatural. SvD quotes a representative of a consumer organization denouncing it as dangerous and says food producers should remove it. Of course they will, if it gives them bad press. The trouble is that MSG is quite natural and easy to add by adding tomatoes or parmesan cheese. Hmm, are Italians or people eating Italian food overly obese? And if you want to just add the amino acid, just write "hydrolyzed soy protein" on the label - it is 100% true. If that sounds too chemical, just add soy sauce, it is nearly the same thing.

Fourth, if glutamate in food was a danger we would all be dead. Glutamate is the main neurotransmitter in the brain, and even a slight excess of that in the tissue would likely crash the whole system. But glutamate is also a very common amino acid used in most proteins, making the total intake several times the amount used in the brain. (see this review and this article).

The real issue is of course that glutamate, and the umami taste in general, makes food taste good and makes people want to eat it more. It especially seems to be a way of getting people to accept a novel food. This has been used to get patients to eat healthier food and improve the appetite of elderly.

Now, what is the effect of appetizing food? We tend to eat more, even when we are less hungry. The real issue here is that we have become so good at making cheap and yet tasty food that we tend to overeat. MSG is not the villain, it is just another tool in the toolbox of skilled cooks in their attempt to make what we eat taste well. We could easily get rid of obesity by mandating that food should be bland, expensive and ideally slightly spoiled. Clearly we want another solution. I'm going to ponder what to do over lunch.

September 12, 2008

Mind taxonomies

Kevin Kelly speculates about a possible taxonomy of minds (and in another post discuss different kinds of self-improving intelligences). His aim is to consider how a mind might be superior to ours. Nice to see him rediscover/reinvent classic transhumanist ideas.

Kevin Kelly speculates about a possible taxonomy of minds (and in another post discuss different kinds of self-improving intelligences). His aim is to consider how a mind might be superior to ours. Nice to see him rediscover/reinvent classic transhumanist ideas.

His list is rather random, a mixture of different implementations, different abilities, different properties and different abilities to improve themselves or other minds. Still, it is an interesting start and a good way for me to check what ought to go in my (still unpublished) paper on the varieties of superintelligence. Here is Kelly's list, ordered by me and with comments in parentheses.

Implementation

- Super fast human mind. (the classic "weak superintelligence example")

- Symbiont, half machine half animal mind.

- Cyborg, half human half machine mind.

- Q-mind, using quantum computing (whether this would provide anything different from a classical mind is unclear)

- Global mind -- large supercritical mind mind of subcritical brains.

- Hive mind -- large super critical mind made of smaller minds each of which is supercritical.

- Low count hive mind with few critical minds making it up.

- Hive mind -- large super critical mind made of smaller minds each of which is supercritical.

I find it interesting that he left out pure AI, a mind created de novo. In my paper we also include biologically enhanced humans.

Abilities

- Any mind capable of general intelligence and self-awareness.

- Mind capable of cloning itself and remaining in unity with clones. (cloning is easy if you are software, remaining "in unity" might be much trickier - I guess he refers to clones being able to exchange mental data, which seems to require at least some form of unchanging or lockstep-changing mental/neural structures)

- Mind capable of immortality. (in our paper we noticed that there is a great deal of difference in what you can do with minds that can be run for an indefinite subjective time and the minds that you cannot)

- Mind with communication access to all known "facts." (F1)

- Mind which retains all known "facts," never erasing. (F2) (not clear whether this is even consistent; when a "fact" is disproven, does it leave a mental audit trail?)

- Anticipators -- Minds specializing in scenario and prediction making. (overall, specialized minds have interesting potential)

A rather mixed bag of abilities.

Properties

- Mind with operational access to its source code. (or its neural underpinnings. Not necessarily useful)

- Super logic machine without emotion. (which might be inconsistent)

- Storebit -- Mind based primarily on vast storage and memory. (the extreme would be the blockhead; I actually regard blockheads as intelligent)

- Nano mind -- smallest (size and energy profile) possible super critical mind. (I guess supercritical refers to self-improving)

- General intelligence without self-awareness. (might be unstable, and become self-aware. See the first chapter of Greg Egan's Diaspora)

- Self-awareness without general intelligence. (probably not too hard to do)

- Borg -- supercritical mind of smaller minds supercritical but not self-aware

- Mind requiring protector while it develops. (overall, the issue of how vulnerable an entity is and how much development it needs is important)

- Very slow "invisible" mind over large physical distance.

- Vast mind employing faster-than-light communications.

Improvement abilities

- Guardian angels -- Minds trained and dedicated to enhancing your mind, useless to anyone else.

- Rapid dynamic mind able to change its mind-space-type sectors (think different)

- Self-aware mind incapable of creating a greater mind.

- Mind capable of imagining greater mind.

- Mind capable of creating greater mind. (M2)

- Mind capable of creating greater mind which creates greater mind. etc. (M3, and Mn)

I think one can clearly improve on this, and it would both be fun and useful.

What we really need is a better understanding of what would go into self-improving intelligence, since if there is any hint that it could indeed lead to a hard take-off scenario then a lot of existential risk concerns become policy relevant. At the same time being open for the diversity of possible minds is important, since there are likely plenty of choices - and some might be closer than we think.

In my and Tobys paper we argued that there are a few basic dimensions of superintelligence: speed, multiplicity (the ability to run copies in parallel), memory (which includes a sub-hierarchy of kinds of better working memory that likely closely relates to intelligence), I/O abilities and the ability to reorganize. These allow some superhuman abilities even using fairly simple "tricks" like running a group of subminds, creating internal organisations with division of labor just like organisation managers do, and "superknowledge" where the "thinking" is actually data-driven and due to the production of society at large. Different kinds of base minds are differently easy to upgrade along these dimensions, with biology having strong speed limitations, AI and brain emulations being suited for multiplicity, cyborgs by definition being better at interfacing new systems etc. Different kinds of problems would also benefit from different kinds of expansion, suggesting that even if the overall result is an increase of effective general intelligence in practice there are advantages and disadvantages for any particular problem that makes certain mind designs better for them. Ultra-fluid minds could of course adapt to this, but there is a cost to being fluid too.

Given that the collective minds formed of ARG-players can clearly form cheap kinds of superintelligence (or maybe supercompetence is a better word?) today, understanding the space of minds can be quite crucial and profitable.

September 10, 2008

My essay survived!

An essay by me, Jason G. Matheny, and Milan M. Ćirković, How can we reduce the risk of human extinction? has just been published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Feels extra suitable given the LHC test lap today.

An essay by me, Jason G. Matheny, and Milan M. Ćirković, How can we reduce the risk of human extinction? has just been published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Feels extra suitable given the LHC test lap today.

The discussion on Skiften about global catastrophic risks the last week has been pretty interesting. We have been discussing the problem of abstract risks, particle physics of course, what disasters sell best in media, whether we benefit from evil people causing disasters that we then tighten our defenses against, fat tail issues, and the difference between "classical" disasters and "relativistic/quantum disasters". I think Alexander Funcke had the most quotable conclusion: "Eggs and baskets should be written as plurals when we are dealing with the survival of the species".

September 02, 2008

The Shift in Disasters

This week I'm responsible for "veckans skifte", the theme on the blog Skiften. My subject is the changes in global risk (in Swedish). This is a continuation of previous looks at global catastrophic risks this summer.

This week I'm responsible for "veckans skifte", the theme on the blog Skiften. My subject is the changes in global risk (in Swedish). This is a continuation of previous looks at global catastrophic risks this summer.

I find doom-mongering both depressing and annoying, but at the same time there seems to be serious cognitive bias against recognizing rare but serious risks. I think there is also some form of approximate "conservation of worry" in society that makes different risks compete for attention. The result of the dominance of climate change as The Big Risk is that people underestimate many of the others, even when they are completely uncorrelated. At the same time there is clearly more than a little irrational millennialism around, biasing people towards focusing on the nice, dramatic risks. But the ones I fear are the total unknowns.

If there is a future great filter as explanation for the Fermi Paradox (unless it is some evolutionary convergence that turns us into a quiet M-brain civilization), we should expect it to strike relatively soon. Within a century we could definitely spread across the solar system and be on our way beyond, becoming quite hard to kill off as a species. Hence whatever threatens us must be striking before then. But we should expect that all other (now lost) alien civilizations have tried to reduce the risks facing them, including taking the great filter into account. So the filter, in order to be a cause of the great silence, must be something no civilization can plan for, yet extremely reliably deadly.

To me, this argument suggests that we should be concerned with a category of unknown unknowns as major risks. We do not know what they are, and maybe they are even unknowable before they happen. But we better find a way around them if we want to survive.